![Lorenzo Steele]()

“I had buddies that couldn’t take the job and wound up quitting because of the mental abuse and, sometimes, physical abuse,” says Steele. “You could be responding to a fight, not knowing that they’re setting you up to stab you with a shank. It’s a very dangerous job. Corrections officers don’t have guns. At that time we weren’t even carrying mace. The only weapon you really have is your mind — how you used it dictated if you were going to have a good 8 hours or a bad 8 hours.”

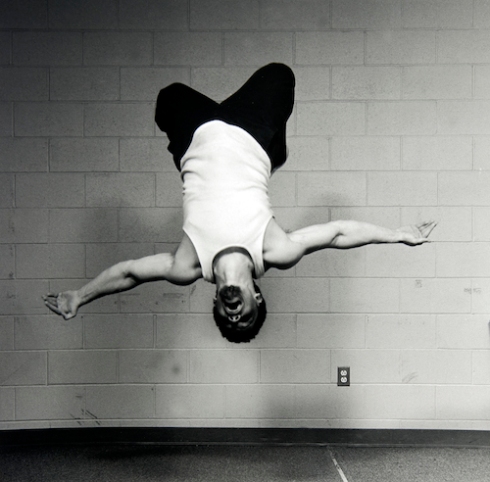

COP TURNED ADVOCATE

Lorenzo Steele Jr. worked as correctional officer on Rikers Island between 1987 and 1999. Most of his time was spent in the juvenile units. When the officers had retirement parties and other events, he was the one with the camera. In 1996, Steele began talking his small compact film camera into the units and making photographs of the dirt, the filth and the despair. All without any official approval. As part of his work, he also made evidence photos of injuries following violence inside the Rikers Island.

WARNING: THIS ARTICLE INCLUDES GRAPHIC IMAGES OF MUTILATION

When Steele decided to leave the job, his “leap of faith” took him back to community instruction. As founder of Behind These Prison Walls Steele gives public lectures and brings pop-up exhibitions to New York neighbourhoods. It’s a mobile show & tell to shock and educate youngsters on the destructiveness and terror of prison. Steele estimates he has made close to 1,000 presentations in schools, churches and community centres since 2001.

I came across Steele’s archive when some of his images accompanied For Teens at Rikers Island, Solitary Confinement Pushes Mental Limits, a Center for Investigative Reporting article that was also adapted and cross posted to Medium as Inside Rikers Island, part of the excellent ‘Solitary Lives’ series.

It is very unusual for photographs made by correctional staff to surface, let alone for there primary use to be as tools for street-side exhibition and engagement. I called Steele and asked him some questions about his self-propelled cop-to-advocate career change, his motives for making the images, the efficacy of his methods and what we need to start doing differently to decrease the numbers of kids we lock up.

![Lorenzo Steele]()

Q&A

Prison Photography (PP): When did you decide you wanted to be a correctional officer?

Lorenzo Steele (LS): At 21 years old I took a [New York] City test. At that same time I was a para-professional for the New York City Board of Education working with Middle School children. I was there for 8-months and loving the job. I got a letter from the city saying that if I could pass a physical, if I could pass the psychological, if I could pass the drug test, I could become a correction officer.

The only reason I became a correctional officer was because it was paying more money than the Board of Ed. I didn’t know I had to experience the system for 12 years, in order to know the system, and later to help people avoid the system.

I’m 22 years old, and it is just a job — no one in my family went to jail. In the neighborhood I grew up in, nobody went to jail.

![Lorenzo Steele]()

The academy was 2 to 3 months at that time. They could never prepare you mentally and physically for what you were about to experience working in a prison. On the first day took the ‘on the job trainees’ OJT’s into an actual facility. Now, they would tell you things — don’t talk to the inmates; don’t stare at the inmates but that was about it. I was afraid, but later I realized that in a prison you can not show fear because you will be manipulated. OJT was about 2 weeks, and after that we were assigned to our facilities.

I worked the C-74 Unit, the Adolescent Recession Detention Center (ARDC) for 14 to 21 year olds. Within that age range, of course, half are adolescents and half are adult inmates. One day you’re working with the adolescents, the next you’re working with adults. I dealt with mental health issues, behavior issues, socio-economical issues. I found out what our people actually go through and why they come to jail.

PP: What were your early impressions of the job?

LS: I’m young, I’m making good money. I have my own apartment, but I have the mind of an officer now.

Can you imagine sitting in a day room with a capacity of 50 inmates and you’re one officer that’s in charge? Your main function is to make sure they don’t kill each other or rape each other and if you see a fight you push a personal body alarm. Depending on which housing area you are in, you can sit there sometimes for 8 hours. I remember the day when I thought, “I can’t do this for twenty years. There are bigger and better things out there for me.”

I’m a photographer. I wondered what I could do legally. I started formulating a mentoring program. I used to volunteer my time in schools as a correction officer and share my insight on what the prison system’s really like. The average person doesn’t really know until its too late. It’s my mission to let these young children know that jail is the last place on earth they want to be.

PP: Do you consider yourself fortunate in that you came to that decision? Because for a lot of people in a lot of jobs, sometimes the stress is so high and the options seem so few they can’t even step back for a minute to see a change in circumstances.

LS: It was very rare for anyone to just resign from the department, unless they were brought up on charges. It was almost unheard of. People asked, “What are you gonna do? This is the best job.”

The last day that I knew I was going to be there, I walked around the jail and I grabbed a little object where I could and wrote on the wall. I carved my name in some wood objects and on some metal doors.

It was around the time of Mother’s Day. My Grandmother was in town and I took her to church. Sometimes, the preacher is actually talking to you. He said, “If there’s anything on your mind just leave it behind you, step out on faith.” That next day, that Monday, I went downtown and turned in my shield, turned in my gun.

PP: What year did you resign?

LS: 1999.

PP: In between which years did you make photographs in Rikers?

LS: I began maybe around ’95 or ’96.

I was the photographer for COBA, the NYC Correctional Officers Benevolent Association. People retire or you have parties or special events. I always had a camera on me. After that, I used to take pictures of inside of the prison not knowing that I was to turn it into an enterprise to save people from going into the jail.

I had a camera with no flash. Can you imagine taking out a camera? You’ve got 200 prisoners coming down the corridor to the cafeteria — they’re going to see the camera going off so I had to disguise it somehow. You get an adrenaline rush knowing that you can’t get caught. Once that shutter button is released its almost the best feeling in the world. Its like a high once that shutter button goes off and you’ve captured that image. And you know.

![Lorenzo Steele]()

PP: Where did you keep the camera? In an office or did you take it home with you every day?

LS: I had it in my pocket. Sometimes I would take pictures of the officers in their uniform because the average officer never really has a picture of himself in uniform. It was a good time back then because the camaraderie was great. We had one team; the officers, the captains, the deputies, the warden. We were all one team back then, but you couldn’t do it today because after twenty years things change in the department.

PP: What type of camera did you use?

LS: A 35mm. One of those CVC store cameras. Digital cameras weren’t even out then. I put some black tape around the flash and disguised it almost like a cell phone or a beeper.

PP: How many photographs do you think you took, in total, inside the prison?

LS: Over 200 photos. Shots of prisoners in cells, of the solitary confinement unit, pictures of prisoners who were physically cut. In colour. You can’t imagine the power of those images when I show the kids: “If you don’t change your ways, this could happen to you.”

![b]()

LS: Children cannot relate to prison, yet they see the negative violence on television and sometimes a rapper will glorify prison. Some rappers are promoting violence, promoting gang activity, and that’s some children’s reference to the criminal justice system.

But, once you step foot in that criminal justice system your life changes forever. Sometimes they might not even make it out. At 15-years-old we’ve had adolescents that end up taking 25 years with them upstate because they caught jail cases cutting and stabbing individuals while they was on Rikers Island.

![Lorenzo Steele]()

PP: How do you exhibit those 200 photographs to the public?

LS: It depends on the audience. I have a lot of graphic images so I don’t put those in the schools with the kindergarten kids and the third graders.

I have select images that I use when I exhibit on the sidewalk in at-risk communities. About 20 images at a time but it depends on where and what message I’m trying to get out.

![]()

PP: I’ve seen only a few images like the ones you’ve published. One example is the selection of images leaked by a Riker’ Island officer to the Village Voice two years ago.

We don’t see many images shot from the hip. If we do, they’re usually anonymous. Such images do exist but one must work hard to seek them out. How many people see your presentations? Are people shocked? Surprised? Do people respond to the images in the way that you hope they will?

LS: The first time they see the images, yes, they are shocked, especially students. Students that I deal whether in the church, in schools, in the community, are shocked. Images are powerful but the knock out blow is information, the experience, that actually goes behind what’s in that image.

PP: How dangerous was Rikers? In the 12 years you worked there how many incidents of serious assault and possibly even murder occurred or occurred on your shifts?

LS: Let’s talk about the adolescents first. Rikers Island was considered the most violent prison in the nation. We used to average sometimes 50 to 60 razor slashings a month. Slashing with the single edge razor blade. Cut somebody over the face multiple times inside. There was a lot of blood.

When I went into corrections, I didn’t like the sight of blood [but] I saw so many people get cut that it became normal. I was so desensitized. And that’s scary because that normalcy meant somebody had a scar on their face for life and for every cutting there was a repercussion; if a prisoner got cut he had to get revenge on the other guy and catch another jail case.

PP: I have no idea how politics, street politics or gang culture — in or out of prison — work in New York today let alone in the late 80s and 90s. Over your twelve years, was there consistent gang activity or did it change?

LS: In ’87, there weren’t gangs in the New York prison system. In the early ’90s, we realized we had a gang problem in the prisons. The gangs had their own language. 300 prisoners in the cafeteria and five officers. We had to learn the language real quick and that is what established the Gang Intelligence Unit. By conducting cell searches, we would get the paraphernalia and the by-laws of the gangs

Later on, they flipped gang members into telling the department what the language meant; that’s how the Department of Corrections infiltrated the gangs. We passed the information on to NYPD.

It was very dangerous. You had to be on your toes all the time. The gangs recruited younger people whom they would force sometimes to do harm on officers or do harm to prisoners. We did the best we could.

One of the blessings was that I always had good supervisors. When the captain said ‘go’, you went, and when he said ‘stop’, you stopped. You put your life in the hands of your captain; it’s almost like being in a war. I am old school. That’s what really kept us on top of the prisoners. The jail would never be overrun because you had a select group of officers that demanded respect and that knew how to take care of the business without anybody getting hurt. When prisoners saw that select group of officers, nothing was going down that day.

![Lorenzo Steele]()

Part of being a Correction Officer is knowing your prisoners and you always wanted to know the gangster, you always wanted to know the person who was running the housing area because that’s the one that you would use, you know. “Listen man, while I’m here today, nothing’s gonna go down. Tell the boys man to shut it down while I’m here.”

PP: Clearly, I’m opposed to prisons as they exist. I think we lock too many people up and I think when we’re locking people up we’re not providing the right sort of conditions or services for them. Obviously, what goes on in the jails and prisons relates to outside society. The reason you do your work now, I presume, is because you see that link between poverty, what goes on in the neighborhoods and what happens in the jails.

What do we need to do better? How do we rely less on incarceration and when you must imprison people, how do you make it safer for everyone in the place? How do you stop people from coming back? Do we need smaller prisons, do we need more money, do we need different sentences for different crimes?

LS: It starts before prison. I worked in the neighborhoods classified by criminal justice books as “high-crime areas” and it starts with parenting.

Bill Cosby said on National TV that we have parents more focused on giving their kids cell phones, expensive gear and expensive pants. And they condemned Cosby. They found some black guy on CNN to come on and say ‘Cosby, you are wrong.’ But he was right. Unless you are inside the school system you wouldn’t necessarily know.

That’s why I hit the streets. I try to let the parents know that without that proper parenting their child has more chance of going through the criminal justice system.

Imagine being in a first grade class in an impoverished neighborhood (it depends on the school district) with 30 to 35 students in one class. 1st grade. Half the children can read, half the children cannot read, now you have one teacher. How is that teacher going to really teach? There’s two different dynamics going on in that classroom. We have children across America that are coming into the public school system unprepared to learn.

![INMATE PHOTOS1_0032]()

LS: Poverty is a crime, because poverty comes with where you live. Those in impoverished neighborhoods are subjected to crime, shootings, and drugs, and then children have to go into a school system that doesn’t have the necessary resources. It’s a ticking time bomb.

Unless a parent or guardian is there to break down that math homework, for them, some children don’t know what’s going on. Unless there’s a parent there that could check the homework that the teacher gives every night. Its not going to get done. There’s a lot parents in poorer communities who are uneducated themselves. Look at the statistics coming out of poor neighborhoods — many young adults are not finishing high school and are not going to college. If a parent is not educated, then probably education is not talked about in the home.

The point of attack, strategically, needs to be that early childhood.

![]()

PP: Parenting and education. I can agree. But we can’t roll back the years’ generations to correct past mistakes. So what about the situation as it stands now? Say, you have a 15-year-old who’s acted out, he’s been pulled in by the police, he’s got a serious charge over his head. Is Rikers Island the best place to deal with that kid? Is Rikers Island the sort of institution in which — while they are kept away from the public for public safety — they themselves are kept safe?

LS: If you break the law there are consequences. There are necessary disciplines in place so we have a civil society. But is it Rikers Island or is it a juvenile detention center?

If you would have asked me this question as an officer, I’d have said, “Rikers, yeah.” But, now, when I go into the communities and hear what the parents have to say about a lot of these children just mimicking their parents, I wonder is that child at fault? Why did he steal that cell phone? Maybe his father was a thief, or maybe they don’t have structure in the home. Maybe there needs to be a place where a child’s whole history needs to be examined? What’s going on in that child’s home. Does he have a support system? He lives in a high crime area, how much do we expect him to succeed?

![Lorenzo Steele]()

LS: Yes, I feel there needs to be places where children can go to receive those special considerations, not thrown into a place like Rikers Island in which you’re housed with murderers.

Let’s create places and bring in the necessary mentors. And I’m not just talking about doctors in psychology. Sometimes, it takes the correction officer. Sometimes, it takes that guy that did 25 years in jail.

Create a first offense type place. “Young man, we give you a year. If you do the right thing in this place we’ll seal your record, but if you don’t, you gotta go to the next level.” Sometimes, some people have to go through that prison system if they’re going to turn their lives around.

Create a place where they could come in and get properly mentored to. You understand? Some people have degrees and others not, but there’s only a select few who can really get through to these children.

PP: So, the prison system is too rigid?

LS: It doesn’t always work. Prisons are putting way too many adolescents with mental health problems behind bars. They’re banging on the cells for 3 or 4 hours. These young children need advocates. They can’t speak. Not too many kids are writing a letter to mommy saying, “I’m thinking about suicide tonight; being locked in a 8×6 foot cell for 23 hours, I can’t take it no more.”

![Lorenzo Steele]()

PP: Your photographs were used in an article by the Center for Investigative Reporting about solitary confinement. Over your time as a correctional officer did you see the use of solitary for youngsters increase, decrease, or stay the same?

LS: We had one unit, about 66 cells. Prisoners that cut, stabbed, or assaulted officers, were locked in solitary confinement.

Warden Robinson implemented a program called Institute for Inner Development (IID). The warden put together a team. Hand-picked. A select few that you could trust and you knew they weren’t going to violate any prisoners rights. We did two weeks of training and took it to a select housing area. We transformed that housing area. Imagine going from 50 slashings a month, [among the] adolescents, to zero for four years.

Programs work if you can get the necessary personnel to properly run and maintain them. When we ran the IID program, we took another housing area — a hundred more prisoners — then another housing area. Eventually, we had 200 prisoners in the nation’s most violent prison in America and and next to no violence.

PP: What was different about that program? What was it that you provided the youngsters?

LS: I love children. I’m a disciplinarian, I love reading, so I had tons of knowledge about slavery and the connection between slavery and incarceration, so when you start talking about this new thing, they just love it. These 14, 15, 16 year-olds didn’t have any type of discipline at home, didn’t have the male role models at home. “This is what men do young man. Pull your pants up. Grown men do not walk around with their pants down.”

PP: So it was more about developing different interactions between the correctional officers and the prisoners, and changing the culture within the unit?

LS: Out of all of those officers, twelve officers, we had no psychologists, no therapists. We were the psychologists we were the therapists. Just because you have a degree that doesn’t mean that you can work in an area like that. There’s a lot of passion that’s involved in that.

![Lorenzo Steele]()

![]()

PP: After you resigned, when did you begin exhibiting the photographs?

LS: I detoxed for about 8 months, just not doing anything. From being on the drill to taking it back to normal. Then I started going into the schools and just sharing my information.

PP: With the images?

LS: I laminated some 8×10” color prints and put them on the blackboard. Then I got a laptop and a projector, and went from holding the pictures in my hand to projecting them agains auditoriums and classrooms walls. My first printed use of the images came in a 2005 Don Diva Magazine feature. They gave me 5 or 6 pages. I provided my phone number. Soon after, a police officer who worked with youth called me and asked, “Could you come in a talk to my youth?” That was the start of giving back.

PP: How do you evaluate your work?

LS: Seeing that look on somebody’s face when they think they know what jail was like, but then I show them the reality. Talking to 500 students in an auditorium and asking them, “Is this new information?” and they all say yes. Many of them have to make a change right there. For others its going to take longer to make that change.

PP: Is what you do anything like Scared Straight!?

LS: I’m not trying to scare you straight I’m trying to inform you straight.

When you’re looking at somebody and they got a thousand stitches on their face, the shock is there but along with the shock is the information behind it. Prison is a violent place and the criminal justice system is a for profit agency and so I break down a lot of information within the program.

PP: What images do we need to see?

LS: We need to see the graphic images of the young guy that was in solitary confinement unit who just cut himself with a razor blade because that was the only way that he could get out.

![Lorenzo Steele]()

LS: We need to see the images of a young girl in shackles walking down the corridor with a hospital gown on. We need to see images of somebody crying in their cell at night and the only reason he’s in the cell is because his parents didn’t have the money to bail him out. We need to see those images of the abuses, we need to see the dirt, we need to see the filth.

We need to see the pain the officers go through — the officers that get cut and the officers that get feces thrown in their face hoping that they don’t have Hepatitis. An image is what stays in the mind. Every time you think about doing bad you need to think about that image.

Hollywood uses images too to glorify the rich and powerful with the jewelry on their neck. But it is fake. I use images to bring awareness to what really takes place behind bars and what young adolescents are actually going through. Everyday. It has to be traumatic.

Is the prison system still in the business of rehabilitation? That’s a question that needs to be asked in the Department of Corrections nationwide. Are prisons and jails in the business of rehabilitation? Yes, he did commit a crime, but does he have to be put into a cell for 23 hours. Is that rehabilitation? Or is that torture? We have to define cruel and inhumane treatment. We have to bring up those: terms, rehabilitation or torture.

What we do with this young child while we have him here for a couple years could make or break him for the rest of his life. There’s volunteers that go into the prison and mentor. Recently, I had the week off so I went back to Rikers Island, and did some workshops, talking to the kids. I felt obligated because we’re in a place that could make or break them. Some are going to the street. Some are going upstate. If you’re going to the street, prepare their minds while they’re here. If we’re trying to rehabilitate.

PP: Over the 12 years that you’ve been doing this work, if you can estimate, how many times have you presented to groups speaking and how many times have you presented images?

LS: I’ve done close a thousand presentations — in churches, schools, and sometimes putting them on the streets. Just taking the images right to the high crime areas and putting them right on the sidewalk. People in the poor neighborhoods are not going to go to the museum so I bring the museum to the streets.

PP: Thanks, Lorenzo.

LS: Thank you, Pete.

![Lorenzo Steele]()

Filed under:

Activist Art,

Amateur,

Institutional,

Visual Feeds Tagged:

Behind These Prison Walls,

COBA,

Juvenile Detention,

Lorenzo Steele,

New York,

NYDOC,

Rikers Island,

Solitary confinement ![]()

![]()